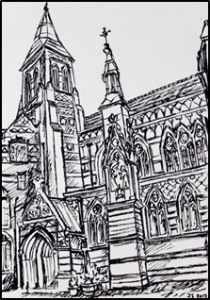

I was in London with a spare hour before my train back to Biggleswade, so popped into All Saints’ church, Margaret Street (above), writes Peter Mann. It was built by William Butterfield (1814-1900), who restored St Denis’ church, East Hatley, in 1874, hence the interest.

Many view it as Butterfield’s masterpiece. It took ten years to complete between 1850 and 1859 and cost £70,000 (around £7m in today’s money). Good value for a complete church, although, as I discovered, a lot of additions were made after it was ‘finished’, some under Butterfield’s direction, so what we see today isn’t how it looked in 1859 – there’s a complete wall of ’tiled pictures’ in the north aisle (1873); other tiled panels and the terrific stained glass are also later.

All Saints’, Margaret Street, London – the interior, looking towards the magnificent altar piece. The church, designed by William Butterfield in 1849, was completed in 1859. Click on the pictures for larger images.

While Butterfield designed all the tiles and much of the stained glass, other well known names were also involved, some working under Butterfield’s direction, notably Alexander Gibbs and Michael O’Connor (glass) and Sir Ninian Comper, who took over architectural duties after Butterfield.

It is certainly a fantastic example of mid-Victorian church architecture, inside and out, for the immediate impression is a building with virtually every surface, walls, floor and roof, being decorated: different colour bricks on the outside and a profusion of tiles, stained glass and much more on the inside.

It is so very different to St Denis’ church in East Hatley – as classically Butterfield in its own way as All Saints’ is a leading example of the radical transformation which hit church building in the mid-19th century.

The difference is in East Hatley (as in St Giles’ Tadlow, which he restored around 1860), Butterfield was working with a 650 year old building (at the time) and was, perhaps, still smarting from criticism of having ‘overdone it’ at All Saints’.

Whatever, while staying with his belief churches should be inclusive for all worshippers (the radical thing in St Denis’ was replacing the box pews with standard seating), he felt country church architecture and decoration should be toned down, more so in St Denis’ than St Giles’, for although there may have been budget constraints with St Denis’, the drawings of ‘our’ church (now in the Getty Research Institute Library in Los Angeles), show admirable restraint; the Friends of Friendless Churches, which owns St Denis’, is expecting to restore the chancel to how Butterfield left it – an exciting prospect.

The big mystery about St Denis’, though, is why such an architectural star as Butterfield would have wanted to involve himself in the effort of restoring what must have been a pretty dilapidated building in an obscure corner of south Cambridgeshire (other than to please Downing College which owned the church at the time).

He was still fiddling with All Saints’, had just about finished Rugby School chapel (1872) and, come 1874, when he restored St Denis’, he was in the middle of building Keble College, Oxford (left, 1868-1882).

Like All Saints’, Margaret Street, both chapels were built in his classic ‘holy zebra style’, as critics dubbed it – indeed, much of his new build included this feature.

But how did he have the time and inclination to deal with St Denis’, especially after discovering it needed a completely new roof? It’s known he had six office assistants – he must have been quite a task master and they must have been working very hard 24/7!

But back to All Saints’, for it is a complex piece of design and architecture.

All Saints’ is a large church on a cramped site – the free Brief guide (available as one walks in) is remarkably informative and useful: the Parish Office has kindly given its permission to reproduce the text and wonderful drawing of All Saints’ (below), although, sadly, they don’t know who wrote it or drew the picture (a shame as both are very good). Thank you, anyway.

All Saints’ is a five minute walk from Oxford Circus Underground. Full contact details are:

All Saints’, Margaret Street

7 Margaret Street

London

W1W 8JG

020 7636 1788

office@allsaintsmargaretstreet.org.uk

www.allsaintsmargaretstreet.org.uk

Open:

Monday to Friday and Sunday 7.00 am to 7.00 pm

Saturday 11.00 am to 7.00 pm

All Saints’, Margaret Street – a brief guide 2020

Text of the Brief Guide available, free, on entering the church. Our thanks to the Parish Office for allowing us to reproduce the text and drawing.

How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven. GENESIS 28: 17

History

The foundation stone of this house of God was laid on All Saints Day, 1850, by Dr Edward Pusey, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement: responsible for the Catholic Revival in the Church of England.

The site was previously occupied by the 18th century Margaret Chapel, to which the Oxford Movement’s principles were introduced in the 1830s. It attracted a considerable congregation, including both the future Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, and the architect William Butterfield, who was to design the new church.

Butterfield’s plans fulfilled the desire of the influential Cambridge Camden Society (from 1845 the Ecclesiological Society) for a ‘model’ church demonstrating its ideal of church design and furnishing.

It was also to be a model of the practice of the Oxford Movement’s ideals of daily worship, preaching and teaching, pastoral care and spiritual direction. It would have a resident college of clergy, and a choir school (closed in 1968).

A tour of All Saints’

Butterfield’s ingenuity in fitting the Church, the vicarage and (originally) the Choir School around an open courtyard, into a space just over 100 feet square, is remarkable.

The internal proportions are such that one is quite unaware of the true dimensions, struck only by a sense of spaciousness. The Nave is 63 feet long and the choir and sanctuary 38 feet.

Over the last 20 years a restoration programme has replaced the roof, cleaned the interior and installed comprehensive new lighting.

Our tour begins just to the left of the main door and then works around the Church clockwise.

Baptistry

Make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. MATTHEW 28: 19

Butterfield’s fine marble font and, behind, the Paschal candle stand, a copy of the one in the Certosa in Pavia, Italy.

The Baptistry contains a fine marble Font for the sacrament of Baptism: our entry to the life of the Church. On the walls you can see Butterfield’s decoration of incised inlays and marble roundels.

Look up to see more of Butterfield’s original paintwork: the pelican in her piety. The original window was destroyed by a bomb blast during the Blitz. In 1997 a window which had been hidden behind the organ for most of the century was restored and adapted to occupy this space.

The Paschal Candlestand is a copy of that in the Certosa in Pavia, Italy. It holds the Easter candle which symbolises the risen Christ.

Nave and aisles

Now walk into the main body of the church – around you, the nave arches are supported by pillars of red Aberdeen granite on black marble plinths, and capped with foliate alabaster similar to the gilded carvings in the sanctuary.

Wrought iron light fittings in the aisles, introduced in 2015, replicate Butterfield’s original electroliers.

All Saints’ great west window, designed under William Butterfield’s direction by Alexander Gibbs, 1877.

Look up and left. The great West Window was designed under Butterfield’s direction in 1877 by Alexander Gibbs (who also designed the windows in the south aisle). Its subject is the Tree of Jesse, the Old Testament forebears of Jesus.

Below is a tile-work showing three Old Testament scenes: Moses and the serpent, the sacrifice of Isaac and Melchizedek the priest. All prefigure the sacrifice of Christ. These panels are a memorial to Berdmore Compton (Vicar 1873-86).

Above the arcade to the Baptistry is another, of the Ascension, in memory of Henry Wood, a churchwarden who died in 1890. All the tile pictures in All Saints’ were Butterfield designed.

In the northwest corner of the Church is a window depicting the prophets Enoch, Isaiah and Malachi. Designed by Butterfield, it was produced in 1862 by Michael O’Connor, who was also responsible for the glass in the clerestory (upper windows).

The massive north wall tile picture was erected in 1873 as a memorial to William Upton Richards, first Vicar of All Saints (1845-73).

The central panel portrays the Nativity. The two panels to the left show figures from the Old Testament, culminating in St John the Baptist. On the right are saints of the New Testament and the early Church.

To the left of the pulpit is the Lady Chapel. Constructed by Ninian Comper in 1911, it has fine alabaster figures of the Virgin and Child, St Mary Magdalen, and St Augustine of Hippo. An aumbry safe in the north wall contains the holy oils used in baptism, confirmation and the anointing of the sick.

The pulpit is of multi-coloured marble on granite columns. The geometric designs seen here, and throughout the church, are characteristic of Butterfield. The pulpit cost £400 in 1850, £40,000 in today’s prices. Such lavish expense was to stress the importance of scripture and preaching in the life of the church.

The serene figure of the Virgin and Child, carved in Bruges by Louis Grosse, and was installed in 1924. Candles may be lit here as symbols of our prayers.

Organ

The Organ Chamber lies to the left of the chancel. Built by Harrison and Harrison of Durham in 1910, the Organ itself is a superb four manual instrument, with 65 speaking stops, created to the specifications of Dr Walter Vale, then the church’s organist.

It is still cared for by Harrisons; a major restoration in 2003 included repainting the pipes.

Altar and chancel

Do this in remembrance of me.

The Chancel Gates, and the screens on both sides of the Chancel, are fine examples of ironwork by Potter of South Molton Street. The ironwork screen and gates in the south choir aisle were installed in 2007. Behind this screen is a window by O’Connor.

Beyond the low marble chancel wall is the Choir and Sanctuary. The centrality of the Eucharist in the Church’s life is emphasised by the decoration of the Sanctuary, where the High Altar stands and by the focus on the Altar.

The altar piece you see today is not the original, but a fairly faithful copy dating from 1909 by Comper. The central panels portray the Nativity and the Crucifixion, flanked by the Apostles. At the summit is Christ in Majesty, being worshipped by the company of heaven. In 1914, further panels were added by Comper on the north and south walls. The lower tier depicts the Fathers of the Eastern and Western Churches; the upper child saints and martyrs.

I am with you always.

I am the bread of life.

Above the altar, is the great silver Sacrament House in which the Blessed Sacrament is reserved for the communion of the sick, and as a focus for prayer. This too is by Comper, who succeeded Butterfield as the church’s architect. It is a memorial to former choristers who were killed in the First World War. The sanctuary lamps are based on a design in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

A house of prayer for all nations.

We hope you have enjoyed your visit to All Saints’.

Before leaving, please pause for a moment in its peace, and pray for those who visit, serve and worship here. As we have done since our foundation, we keep a cycle of daily services at All Saints’ [the times are above] – you are welcome to join us.

Finally, as you leave All Saints’, look up at the spire, an outstanding feature. At 227 feet it’s two feet higher than the Westminster Abbey western towers. Clearly visible from Primrose Hill, holding its own against a London skyline much more crowded today than in the 1850s.

Music, more links and photographs

Music Someone was practising on the organ when I entered All Saints’ (about 2.30 pm, 28th January) – and very good they were too.

Music is important to All Saints’: ‘harnessing the power of music to help communicate, explain and explore religious texts’ is part of their traditional approach to their Anglican faith, as discussed on their website (where you’ll also find links to their CDs).

Links There’s lots of information about both William Butterfield and All Saints’, Margaret Street on the internet: here are some key links:

- Home page – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- English Church Architecture – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- Open City Projects – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- Khan Academy – All Saints’, Margaret Street / William Butterfield.

- Tripadvisor – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- Victorian Web – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- Wikipedia – All Saints’, Margaret Street.

- Britain Express – William Butterfield.

- Geoffrey Tyack – William Butterfield / lecture, September 2019

- National Portrait Gallery – William Butterfield / portrait.

- Online Archive of California – William Butterfield / drawings.

- V&A – William Butterfield / chalice.

- Victorian Society – William Butterfield / books etc.

- Victorian Web – William Butterfield.

- Wikipedia – William Butterfield.

Photographs I neglected to take my digital camera with me when I popped into All Saints’, so had to rely on my phone for photography – the pictures are sort of okay, but colour and sharpness don’t do justice to the wonderful church art which is All Saints’, outside and in. Nevertheless, I’ve put them into a photo gallery – link below.

- There are very good photos and a ‘virtual tour’ in the history section of the All Saints’ website: www.allsaintsmargaretstreet.org.uk/history.

Click here for our All Saints’, Margaret Street, London photo gallery.

Page created 8th February 2020; updated 15th November 2024.